Dispatches from Mount Ainslie

Phoebe Lupton

So, here I am on country that isn’t mine, but I still find myself saying that this is where I’m from. On Ngunnawal country, I feel same-same but different. The air is clearer than what I’m used to, so clear you can almost smell something in it. I don’t see any clouds of petrol floating from cars to streets, because there are fewer cars in the streets. And there are stars in the sky. There are no stars in Sydney, just pollution. So-called ‘Canberra’ is Schrodinger’s home: my home, but not my home. There is a Canberra Home that I picture in my mind, and it’s a small house at the bottom of Mount Ainslie, on the Hackett side, with a long driveway and a sugar plum tree. I’m picturing magpies perching on the fence, eager for company. I’m imagining myself walking up a couple of steps to reach the front door, and the whole time I’m surrounded by flowers and, inevitably, bees. The air is laced with the smell of curries and dal and mint in the warmer months, and with wine and Easter chocolate in the cooler months. Its rooms are noticeably ancient. The walls are brown and the bed sheets smell of cold cream. I can tell that someone lived here for a long time, and I can tell that these people are no longer alive. Canberra Home is my grandparents’ home.

*

They ask me ‘Where are you from?’, provoking a discomfort inside of me that eclipses my body . I’m mixed race, so what is the asker really trying to ask about my ethnicity, my cultural ancestry, or my birthplace? Now that I’ve moved interstate, that question triggers a new confusion. I’m the new kid in school and my peers keep popping the question, and I have to analyse their sentences for context clues. ‘Where are you from?’ can mean anything, but ‘Where were you born?’ is coded differently, as is ‘What’s your culture?’ I’m spewing out all the answers that make sense to me in the moment: ‘Australia, but with mixed Anglo-Saxon and Singhalese ancestry,’ ‘Sydney,’ and ‘White and South Asian,’ respectively. But every answer tastes like a lie.

*

I know that nationality and ethnicity are different things, but they seem so intertwined, especially given how white Australians speak about those two things. Since colonisation, Australianness and whiteness have apparently been interchangeable, despite constant claims of multiculturalism. I can’t stop thinking about this during Year 10 History, where post-war immigration makes up a good chunk of the curriculum. I’m looking at a worksheet that my teacher has passed out, lined with various words and their definitions: nationality, ethnicity, emigration, immigration, migration, racism, xenophobia. Many of these words seem to mean similar things, but later in the year my teacher actually provides examples. A black-and-white newsreel showing an Italian man ‘talking with his hands.’ An Australian news reporter referring to British immigrants as ‘poms.’ A woman tearfully reflecting upon her deportation to Papua New Guinea in the 1960s, when she was a little girl.

*

In her widely acclaimed book Why I’m No Longer Talking To White People About Race, Reni Eddo-Lodge interviews a politician who advocates against miscegenation and the birth of mixed-race children. In the interview, the politicians construct one-dimensional characters in the story of racial politics: White people as damsels in distress and people of colour as villains. This is what distresses me the most about white supremacy and white nationalism: its inflexibility. Its strict national and racial constructs. For a right-wing ideology whose proponents claim to sit on the same political side as proponents of freedom, I have gathered white supremacy to be incredibly limiting to freedom. Believers in this ideology want to dictate who should belong to which country, who gets to decide on their own national identity. But I want that decision to be my own.

*

My father considers himself Australian. That’s what he’s decided. He’s no white supremacist, and he values the freedom to make what he wishes out of an identity. I’m not all that different in this respect. When white Australians pop Dad the question, I don’t know how he answers. I don’t know whether he stumbles like I used to or recites a well-rehearsed line like I do now. I know that Dad was born in Canberra Hospital. He tells me he looked like the urchin in the really quite cruel episode of Seinfeld, in which Jerry and his mates are staying with a family who welcome a newborn with a monstrous face. He also tells me that he was born with a shock of black hair, a dead giveaway of his South Asian heritage. (My younger cousin, the second of my Achi’s three grandchildren, was also born with a shock of black hair. I wasn’t, but I went on to grow hair so thick I can barely brush it without nearly breaking either my brush or my hand).

*

There was a time in primary school when the sight of my family would break white people’s brains. I’d enter the room arm in arm with Dad and they’d vaguely double take at his broad Australian accent, and most of the time they’d pop the ‘Where are you from?’ question. But I look like him. Dark hair, a gap between the two front teeth, almond shaped eyes that thin out when I laugh. His skin is darker than mine, but mine is dark enough to be clocked as non-white. On the flip side, I’d enter the room arm in arm with Mum and they’d pop a different question: ‘Were you adopted?’.

*

I’ve established a consistent writing practice, and at the moment much of my work focuses on race. I speak about it over and over again with friends and family, white and non-white alike. For a little while, I think I’m done with the topic. Then, my aunt sends me a clip of SBS Insight on mixed-race people. One of the interviewees shares the same anecdote I just shared: ‘Kids would see me with my mum and ask if I was adopted.’ I share with my aunt that I’ve had to answer this exact question. ‘I always thought that everything was so much better for your generation,’ she says. ‘Just goes to show how little has changed.’

*

Dad and I are watching a Doctor Who episode about Rosa Parks. We see the Thirteenth Doctor (Jodie Whittaker) and her friends Graham (Bradley Walsh), Ryan (Tosin Cole) and Yaz (Mandip Gill) board a bus in 1955 Alabama, similar to the one that Rosa Parks historically boarded. The Doctor and Graham are sent to the ‘Whites’ section of the bus, Ryan is sent to the ‘Blacks’ section of the bus, and Yaz is left confused. A Pakistani diasporic Brit, the bus driver reluctantly codes her as white, belying her true racial identity. Yaz says, ‘They told me I could sit in the white section…not a lot of Pakistani heritage in 1950s Alabama.’ This follows a scene where The Doctor and her friends dine in a pub and a waitress kicks Ryan and Yaz out, labelling the latter ‘Mexican.’ The episode hurts to watch. I say to Dad afterwards: ‘If we were in 1950s Alabama, we’d probably be called “Mexicans” and be reluctantly let into the white section of the bus.’

*

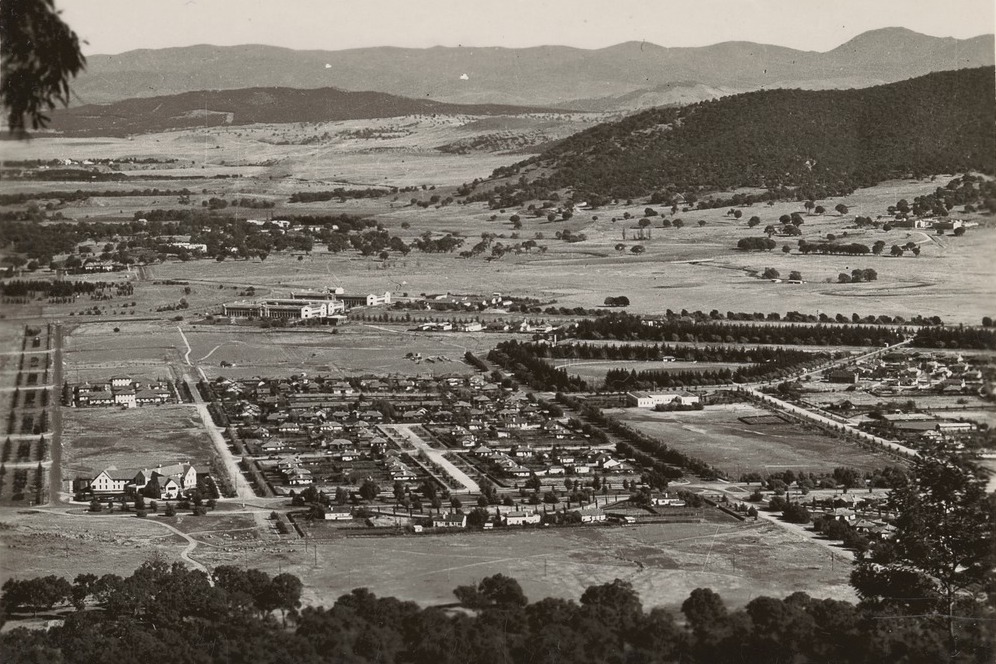

Dad and I aren’t alive in the 1950s, but Achi is. She meets Grandad back in Singapore, then finds her way to Canberra with him. It’s a culture shock of the first degree, not to mention a weather shock. Achi’s familiar surroundings of heat, humidity and the smell of carpet mould have been replaced with dry, cold air and plains of dying grass. It’s the 1950s in capital-city suburbia, so the people she meets are pasty, unlike her previous brown-skinned peers. While before, she’d wade in sound baths of Singhalese, Tamil, Chinese, Hindi, Malay and English, all she hears now is English. This is her second migration. Her first was from Malaysia, her birthplace, where during World War II the Japanese raided the house in which she was raised. I wonder what the house looked like. I imagine it was large, hence why soldiers would occupy it as their headquarters. More importantly, I wonder if Achi ever found somewhere to call home.

*

In her essay for Nikesh Shukla and Chimene Suleyman’s anthology The Good Immigrant, Fatimah Asghar writes about finding home in the United States: ‘I both belong and don’t belong to America. When I’m in America, I’m constantly reminded that I’m not actually from here…But when I’m abroad, I feel the most American I’ve ever felt.’ Asghar’s essay speaks to the loneliness of the immigrant. Dad tells me Achi was affiliated with various Sri Lankan societies in Canberra (if there was more than one). Mum asks: ‘Why did you never get involved with the Sri Lankan societies?’ Dad says: ‘I never felt a reason to.’ Maybe Achi was lonelier in Canberra than in Singapore. Maybe Dad wasn’t any lonelier among Australians as he would have been among Sri Lankans. It’s the classic second- and third-generation conundrum: we are both, and we are neither.

*

Growing up in Westernised, Anglicised Australian society, people pop the question but they also take guesses: ‘Indian?’ ‘Spanish?’ ‘Malaysian?’ I want to cry ‘Australian!’, but I know that’ll never satisfy them. In their eyes, Australianness doesn’t match up with the image of me. Part of me wants to tell white Australians about my convict ancestry. I’m not proud of it, and it doesn’t tell the full story – that I descend from both colonisers and the colonised. I just want to prove to people that I deserve to be here as much as they do.

*

And then I leave Canberra for Dharawal country for a little while, but it doesn’t work out. My apartment feels and smells damp, the walls are paper-thin, and I’m surrounded by a symphony of resies partying and chairs scratching balcony floors. The only place that feels safe here is my aunt’s home. It’s kind of TARDIS-like: looks small from the outside, but feels much bigger once you’re inside. The rooms smell like sunscreen and my cousin’s coconut Body Shop shower gel. The beach is a block away, and when you walk out the front door the sea breeze tickles your nostrils.

*

I realise that home is not static – all the centuries of human migration prove this. Perhaps, home is inextricably connected to family, and therefore that’s the only concrete way you can define it. A place to live plus family (chosen or otherwise) to live with equals home. I feel some semblance of home in Wollongong, Sydney, Singapore, and Bega – even though I’m still sitting here on my bed in New Canberra Home.

*

This morning in New Canberra Home, I look outside my bedroom window and see puddles of water covering the lines of the deck. I open the door and kneel to the ground. I sniff like a dog, and petrichor infuses my system. I’m sensory-seeking when it comes to smell, so petrichor is like coffee for me, especially in the mornings. The leaves are wet, and the trees and bushes are a vivid green. This amount of rain, this amount of greenery, is unusual for Canberra. It’s a new era for my current home, and I want to see it flourish. But then I remember that petrichor is everywhere. I go through my usual morning routine: have a glass of water, take my medication, make a chai latte, get dressed, brush my teeth, moisturise, watch some TikToks. Routines like this one help me nest. They make me feel comfortable and grounded, as if my body is the only home I need. It’s a way to solidify myself within space, similar to what my cat does when she lies on my blanket for a nap or strolls through the garden to get her bearings.

*

There’s a somatic exercise I’ve recently learnt where you imagine yourself on top of a mountain. You feel the soles of your feet press against the mossy earth. You inhale the newly oxygenated air. You examine the horizon and you don’t fall into vertigo, because all the elements of nature are holding you. You’re a part of nature yourself, so you’ll never be lost.

Phoebe Lupton is a disabled creative, freelance writer and social work student. They are an Anglo-Celtic and Sinhalese person on unceded Ngunnawal/Ngambri land. You can find Phoebe’s recent or forthcoming work in Antithesis Journal, Overland, Portside Review and Kill Your Darlings, among others.