DISHONOUR. (Hang Them Up And Bring Them Down)

by Cindy Mititelu

ACT 1

They go out in the day to look for stars.

Hal lets the older man drag him through town by hand. Septimus insists that souls have orbits. He draws maps on clipboards for research. A library of real wealth, he believes. Each report is titled in Greek and stapled three times down the left side. If the findings are particularly thick, he resorts to bulldog clips. There is a tired, old receptionist who works the early morning shift on Tuesdays that doesn’t notice when he takes her stationary. Septimus keeps these files in The Place. It’s easy to find; somewhere that people do not frequent out of want but need. Communal. That’s where they met. In the foggy bathroom mirror, Septimus had drawn a crown over his reflected head. It was wonky and childish, thick lines dripping. A portrait framed by white tiles and white light.

Beside him, another patient brushed their teeth, motions rigid and rushed. Hal spat into the sink and avoided looking into Septimus’ eyes. Hal hated that they wore the same blue gown. A pitiful thing that nobody looks themselves in. It’s offensive, but if he complained, it would reflect poorly on his ‘progress’. He missed his electric toothbrush and shaving unsupervised. He missed being alone, away from men who talked to themselves in bathroom mirrors and played pretend.

*

PREFACE (OUT OF FOUR)

1939

GRAPHITE ON PAPER

Rychenkov had sat down in the metal chair with a practiced smile that seemed to surprise them. Perhaps the previous applicants were too nervous to show teeth. It was a confidence that would be given away after clammy handshakes, but there were no unnecessary pleasantries exchanged. Brodsky and Yuon were a cryptic panel; friends of Lenin, acquainted over frequent portrait commissions. Each interviewee was addressed only by last name – Rychenkov, aged nineteen. The Director and senior faculty member were dismally quiet. The silence dazed him as they scrutinised his portfolio, restless fists clenching and unclenching underneath the cedar table. Their reactions were as calculated as his own artistic selections, humming appreciatively wherever Stalin was featured. His still life studies were of hammers and sickles. Brodsky carefully held up a sketch of Komsomol children waving the Soviet flag, pencil figures glowing beneath the tungsten light – Can you paint, Rychenkov? – and Yuon shuffled through the drawings again. In hindsight, he should have lied. A clock in the room ticked. Brodsky waited for an answer with piercing eyes. Marching soldiers shouted in the distance. Rychenkov, Luon repeated, Ry-chen-kov. Rychenkov. The two artists shared a look. Only twenty were to be accepted this year. Nineteen have already been picked. Mostly painters. Some photographers. The sketchers are always insecure, relying too much on erasers. But this one walked in with the precision of a trained marksmen. Where does he imagine to be in a year? The Germans were barely held back. But an impressive creativity nonetheless, even if it will be short. The boy knew Stalin’s best angles.

*

ACT 2

Hal used to live on the tenth floor.

He took care of succulents and cooked pasta; he listened to the Top 40 whilst driving to his off-duty, civil servant occupation in the morning. He didn’t date because romance becomes uninteresting after thirty. But he often went to the pub on Friday nights with his colleagues because there were special prices for the identification cards they had. Bartenders would either nod with respect or conceal mournful reactions. An unspoken comment in between ‘Thank you’ and ‘Poor you’. His mother had given him the same reaction, asking questions that spoke in between the lines, asking about his day but wanting to know if he’s really coping. She called him often, only to see if he would pick up. Hal let the answering machine reach its limit as friends and family left different versions of ‘Welcome Home!’. It was strange to hear people talk without seeing their faces. In uniform, he hated putting names to faces. He didn’t want to know who they were behind the barrel. He didn’t want to think about the lives they had.

*

ONE (OUT OF FOUR)

1942

BLACK CHALK ON BOARD

Underneath the bed, Rychenkov kept a secret list. Neatly rolled and placed inside an empty sardine can, the names were as valuable as his own. Reminders. When the Wehrmacht attacked Moscow, he pitied leaving it behind at Naro-Fominsk. His hometown fell easily under German occupation. There were many pockets on his uniform that would have fit the small oblong can. He could even tuck the slip of paper between a hem, in the same way cigarettes were hidden up sleeves or beneath boot soles. But the importance of it was not tangible, like gold and cash is. He had not written the list with intentions to keep it; cursive rushed and hard to read from the last minutes of an afternoon lecture, listening only to what was emphasised. Become familiar with them the professor had clarified. There would be another class tomorrow. The list was only a beginning. An introduction. Were you paying attention? a friend had asked as they walked to the bus stop, shaking out limp arms and praising June’s warm sunlight. Students filled the campus, spilling from doors like ants. Movement was difficult to draw. Shadows and highlights imitated dimension, but not action. He tried to draw bullets mid-air at home, after they won the offensive. The old techniques took a while to return. Remember them like you are a child learning your address, Brodksy drilled. Degas. Cezanne. Manet. Monet. Rychenkov! – Yuon often shouted, with necessary force – remember your homework and pay attention to the details. Degas was a quick favourite; a master of candid details. He never found the list, but its order became muscle memory. Degas was at the top. Brodksy passed away before he came back. Rychenkov, he would say, what happened to your best angles?

*

ACT 3

Septimus feeds the pigeons at the bus stop with cereal he stole from breakfast.

Just fists of cornflakes shoved straight into his pockets. Hal had watched amusedly, letting Septimus do whatever it was he needed to before their trip into town. Routines; Hal eats exactly two pieces of toast in the morning. He doesn’t use spread because they all taste the same here. When he gets out, he’s going to buy a jar of peanut butter. The dining hall has a no nuts policy. He can’t wait until he can cook in his own kitchen again. Some of the patients here have candy, but Hal knows he won’t be staying long enough to start keeping contraband. Septimus keeps his own in the bathroom on Level 3. It’s just some odd illustrations on copy paper from the receptionist. He had insisted on bringing them outside today ‘for proof’. Hal had heard his fair share of conspiracy theories, but there’s a fine line between disputing the truth and truly believing in lies. He guessed that Septimus was on duty too, once. Instinct. They were both early risers, a habit drilled in from years of being alert after midnight, manning radio transmitters in bulletproof vests.

On Hal’s birthday – which he told no one of at the ward – Septimus had turned to him in the bathroom with a jarringly clear gaze and began reciting Shakespeare. Hal had spat his toothpaste into the sink and spoke to Septimus for the first time. The quote was one Hal’s father had liked out of context: I will from henceforth rather be myself. Though it had nothing to do with self-expression and everything to do with manipulating self-image, Hal accepted both interpretations. It was his father – who had named Hal after liking the name from a play, who found Shakespeare quotes but never read them properly – that guilted Hal into trying treatment. Sons are supposed to make their fathers proud.

When Septimus echoed the quote in Level 3’s quiet bathroom, hearing those words on his birthday were too coincidental to feign indifference.

*

TWO (OUT OF FOUR)

1943

RED INK, LITHOGRAPH

High-ranking officers stood beside his professors at the ceremony. Half of the graduating class would be appointed under Stalin’s Trophy Brigade as collection supervisors in Berlin. Some walked with a limp to collect their certificates. Most sported new scars; shrapnel wounds and bullet holes where death had nicked them by the teeth. Miraculously, all twenty students survived their services. Because we are Russian! the generals proclaimed as Yuon watched on with shiny eyes. The class celebrated together in their old common room – though the Germans had come close to this part of the capital, their campus was largely intact. Stories and sentimentalities were traded over clinking shot glasses. Rychenkov, our non-painter! – they affectionally greeted him – are you still drawing? There was a shared understanding of loss and defeat that they joked around but did not need to directly address. I snapped all my brushes in half! someone said in a tone that made them all laugh about it. Years ago, they had spread out hopeful portfolios and believed in their passions enough to overlook what would be sacrificed; personal oeuvres hidden behind bookshelves and in attics. He recalled one photography student being approached by Izvestia after their second-year exhibition to be recruited as a war correspondent for the paper. What was it like? he asked at their post-graduation celebrations. Painful. But this is what we must do. Victory had lit new flames for them to follow, but it was a hope that flickered wantonly. Before the night ended, Yuon said his final goodbyes and good lucks. He shook all their hands, still as clammy as when they were nineteen and full of innocent anxiety.

*

ACT 4

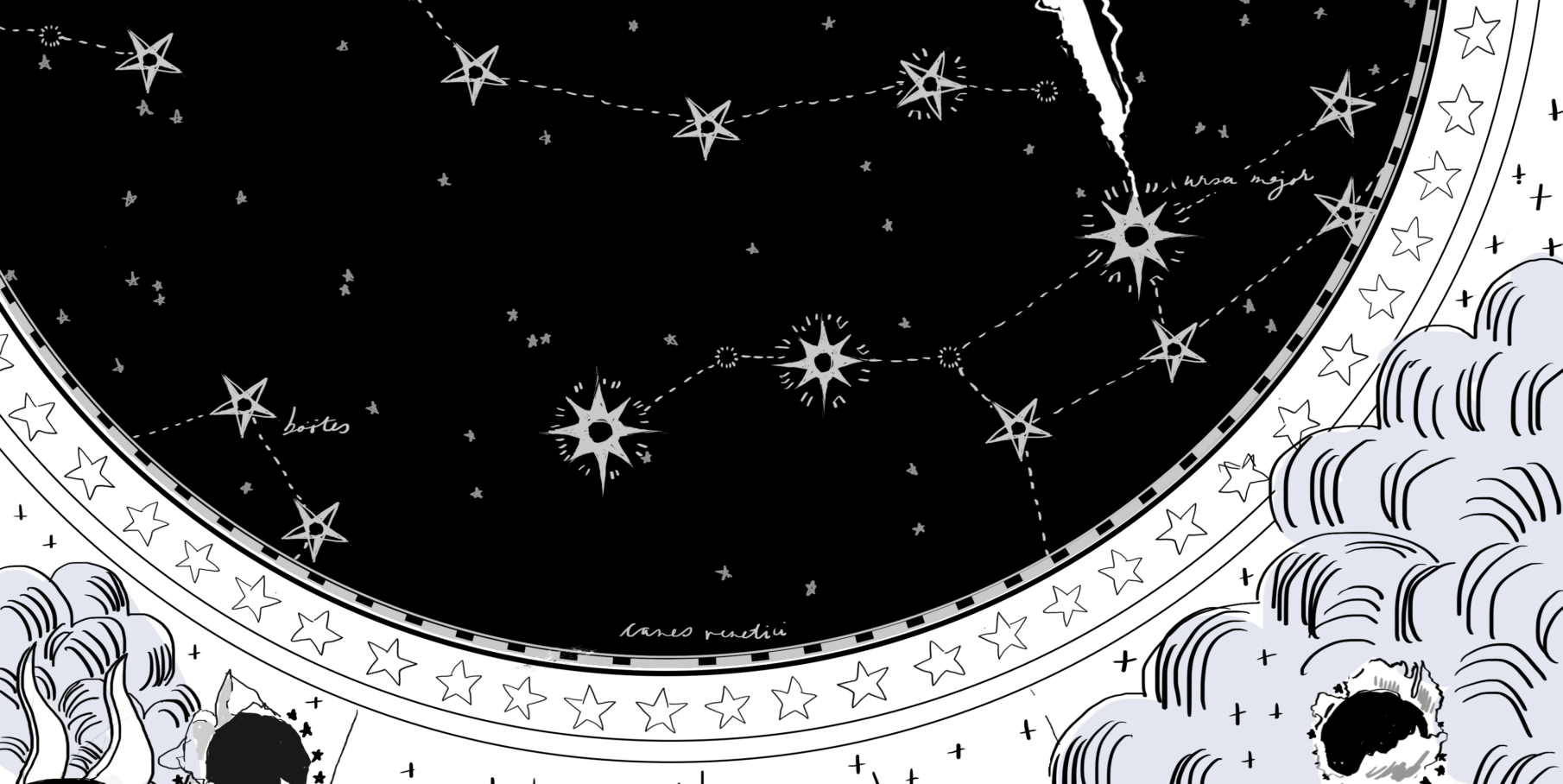

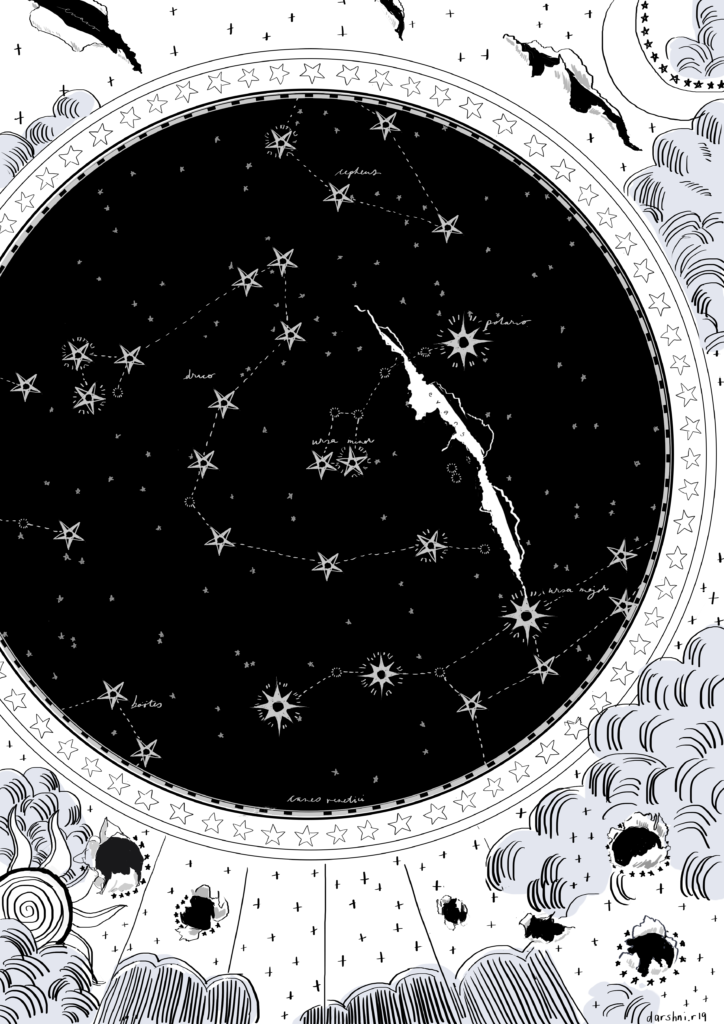

Septimus stabs holes into his illustrations where he says there are stars.

The paper goes shrk-shrk-sHHRK. There is a particularly big rip in one sheet that apparently represents Hal. Tomorrow, Septimus will be transferred to a specialised unit that treats post-traumatic psychosis and Hal will receive an assessment on his final week. He is ready to sleep in his own bed, but he must also face maintaining this recovery; daily counselling now reduced to only fortnightly sessions at a local clinic.

‘Will you from henceforth rather be yourself?’ Septimus chanted at the bus stop. It became both an inside joke and secret code between them. They’ve been at it for almost ten months now. Hal turned to face the other veteran; whose blue eyes were viscerally bright. The pigeons stopped pecking. The wind stilled. As if these things in orbit around Hal were attuned to his weighted pause.

Septimus launches a handful of cereal into Hal’s face. Hal immediately reacts, in an aggressive and military fashion, muscles jerking, insults caught between blue lips. Winter was always colder each year, but never as frigid as taking the night shift on a desert base, concealed under darkness and aiming lasers at curtained windows, waiting for shadowed figures to appear. Sometimes they missed and sometimes they were wrong. Sometimes, Septimus tells Hal about a man named Evans, whose grave is too far to visit but travels through holes in time.

Hal tolerates Septimus when he shouts or acts impulsively. Hal doesn’t put faces to names, but he’s become too familiar with Septimus to make him another metonym of suffering; a quote without context, an ending removed from its story. He brushes cereal out of his hair and collar, listening to Septimus sketch shapes and hum nursery rhymes.

*

THREE (OUT OF FOUR)

1945

GOUACHE ON CANVAS

The removal was a quiet process. Soft murmurs rose above the pews as young soldiers wrapped a large Degas oil in clean woollen cloth. Corner to corner, they gently bandaged the painting, winding thick layers of fabric around it as if strapping a wound. Coloured shards of light filtered through stained-glass windows as careful hands searched through the Dresden museums’ depository. A casually clothed Commissions officer inspected the handlings routinely, her heels echoing on the marble. She spoke with great pauses – Raphael… would be insulted – but was hard-spoken – Are we any better? Of course. At least we still have the Pushkin; Stalin has good taste. Russian commands melted into German conversations; Berlin civilians worked amongst the Soviet trophy brigade in exchange for bread and Burgundy. Packed crates covered every space of aisle and altar, wooden pallets piled high above one another. A pulley was attached to the organ’s loft balcony, knotted rope held taught as they lowered heavy boxes off precarious perches. When the sun had set and it was too dim to work, they paused their labours, communicating minimally; fatigue spoke its own language. It’s a shame, their eyes said to each other, scanning Coreggio’s cloth panels ripped off its stretchers and coiled like a rug. The Russians stopped gawking whenever the Trophy Committee’s deputy did his rounds, whispering warnings between themselves – Be careful with that Degas, Rychenkov has a soft spot for it – as he catalogued each transferal on rolls of drawing paper, badges glinting where they caught the light.

*

ACT 5

The bus pulls in, papers fluttering as Hal scrambles to hold down their strange star maps and soul observations, pigeons flying out at the squeal of braking tyres. If either man was paying attention, they would notice how the rain began pouring down like it did on their last day of a two-year tour together, before the airstrike hit. But these memories have left them like a bus out of town; getting smaller and smaller as they cross the distance.

*

FOUR (OUT OF FOUR)

PRESENT DAY

A Pushkin Museum curator unveils the Degas painting. Patrons applaud as she explains its history, beginning from where it had all come to fruition at the PREFACE…

*

DANCER POSING FOR A PHOTOGRAPHER (DANCER IN FRONT OF THE WINDOW)

1875

OIL ON CANVAS

EDGAR DEGAS

At one point in his recovery, Hal saves up enough money to go on a European holiday; Russia, he decides, because he wants better memories of winter and snow. At the Pushkin Museum, he listens to stories about Stalin’s Trophy Brigade and their selfish honours. The tour group stop in front of a Degas’ oil.

Septimus would be the same, Hal thought as he listened to the story of a man named Rychenkov: who had smuggled the painting into his own train car and removed it from Stalin’s catalogue. It was in honour of all that was lost at war and that – like memory – would never be remembered in the same way again, but as a fragmented narrative; told in acts and parts.

*

Cindy Mititelu is currently a student writer, publishing stories on underground scenes for Savage Thrills (savagethrills.com) and always trying to find her next byline. She sometimes writes fiction… but it hardly ever leaves her desktop. Cindy welcomes any collaborations for future projects or work. Get in touch: cindy.mititelu@gmail.com or @cindeia on Instagram.

Darshni is a Indian-Australian student living in Sydney. She is an editor and illustrator for GREMLINZ Magazine. When she’s not drawing, she can be found nerding out or re-repainting household objects. Get in touch: darshni.raj1@gmail.com or @darshni.r on Instagram.